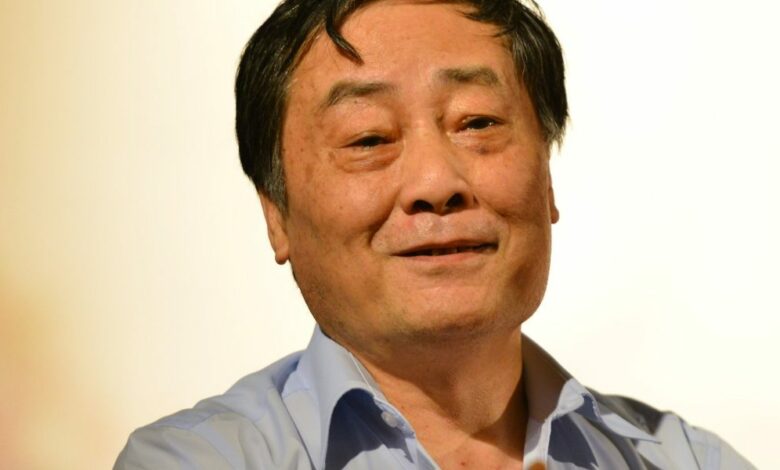

Obituary: Zong Qinghou, China’s richest man and self-made billionaire

Zong Qinghou, the self-made billionaire who became China’s richest man by wresting control of the country’s top beverage brand from Danone, has died. He was 79.

The founder and chairman of Wahaha Group died of illness at a hospital at 10:30 a.m. on Sunday, according to a statement that doesn’t provide further details on the cause of death or the location of the medical facility. The company said on Feb. 22 that Zong was hospitalized for treatment and was in stable condition.

Born before the Communist Party took power, Zong’s life paralleled China’s transformation from a poor and mostly-agrarian country into the world’s factory floor and its second-largest economy. His wealth, which began with a $22,000 family loan, grew into billions of dollars as Chinese people became ever more voracious consumers.

Zong, who never attended high school, was forced to live on a farming commune in 1964 during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. He left in 1978, the year that Deng Xiaoping — having consolidated power as China’s paramount leader — began introducing private business and foreign investment to China, freeing up a generation of entrepreneurs like Zong to dabble in capitalism.

After working as a consumer goods salesman for several years, Zong took over a small shop at a grade school in the eastern city of Hangzhou in 1987. There, he created Wahaha, the beverage brand that would make him one of China’s richest men.

Zong was propelled onto the global stage when he fell out with French food giant Danone, as the two dissolved a decade-long partnership in a flurry of lawsuits and government intervention.

The saga started in 1996, when Zong formed several joint ventures in China with the Paris-based owner of Evian water. The terms of their agreement included the transfer of the Wahaha brand, which means laughing child in Chinese, to the ventures that were 51% owned by Danone.

That partnership grew to a sales peak of 1.1 billion euros ($1.2 billion) in China, before Zong accused Danone in 2007 of trying to take over Wahaha at an unreasonably low price. Danone countered that Zong had violated their contract by setting up Wahaha-brand companies on the side. At the heart of the fight was who owned the Wahaha brand — Danone believed it did as per the terms of the original agreement, while Zong asserted that the Chinese government had blocked the brand transfer application, meaning he still controlled it.

Ultimately, Danone capitulated, agreeing to sell its stake to Zong in late 2009 in a deal brokered by the Chinese and French governments. With 80% control of Wahaha, Zong became China’s richest man by 2012 with a personal fortune of $20.1 billion.

Wahaha’s good fortune didn’t last. Revenue started to fall as the company was slow to adapt to Chinese consumers’ changing tastes away from sodas to healthier offerings like juices and yogurt. Savvier rivals like Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group and China Mengniu Dairy Co. overtook Wahaha with celebrity ambassadors and product placements in Hollywood movies, while efforts to acquire other companies by Zong’s daughter and chosen successor, Zong Fuli “Kelly,” fell mostly flat.

China’s booming Internet industry also soon propelled digital economy entrepreneurs like Alibaba Group Holdings Ltd.’s Jack Ma, Tencent Holdings Ltd.’s Pony Ma and JD.com Inc.’s Richard Liu to fortunes that dwarfed Zong’s.

As the mom-and-pop stores that stocked Wahaha’s drinks and snacks lost business to online shopping, Zong became a critic of the e-commerce industry, accusing it of suffocating brick-and-mortar retailers and of destroying more jobs than they created. He used his membership in China’s legislature, the National People’s Congress, to advocate for more government policies that supported what he called the “real economy” versus the “Internet economy.”

For all his wealth and stature, Zong lived frugally. He dressed simply, and wouldn’t buy new shoes until the pair he was wearing had worn out. Longtime Wahaha spokesman Shan Qining liked to tell a story of sales people at a yacht exhibition ignoring Zong, and being told only afterward that they had snubbed one of China’s richest men.

What few hints there were of his fortune included a taste for Davidoff cigarettes and a $48,000 Vacheron Constantin watch he bought to replace a Rolex — because he had heard that Rolexes were favored by the “newly rich.” He didn’t consider himself one of them, as his fortune was made “one yuan at time,” he said in a 2012 Bloomberg interview.

“For a long time, I couldn’t even afford food and clothing,” Zong said. “I climbed from the very bottom of the society.”

Source link