Fed ends Bank Term Funding Program because emergency funding crutch got too popular—at the worst time for small banks

That includes Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, who predicted more bleeding for some “smaller and medium-sized banks” in testimony to the Senate Banking Committee earlier this month: “There will be more failures,” he put it bluntly.

Powell’s warning came less than a week before the Fed’s emergency funding program, which was designed to help prevent contagion from the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and other regional lenders last year, officially shut down—not least because some banks turned the emergency support into a quick-cash machine.

The Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), as it’s called, provided critical liquidity when many banks were struggling with depositor flight last spring. But with the Fed withdrawing its emergency support this week, banks will have to look to new sources for short-term funding—and that could exacerbate an already grim situation for some.

Regulators have brushed off the idea of any systemic threat to the banking system as a result of a few smaller bank failures, but there is a worst-case scenario that’s worth considering, according to John Sedunov, professor of finance at Villanova University.

“One or two failures in this space would not be detrimental to the financial system as a whole. However, if there would be a large number of failures, then we could be talking about ‘too many to fail,’ which can have important consequences for the system,” Sedunov told Fortune. “There is a case to be made for systemic problems if you have too many banks failing at the same time.”

Sedunov clarified that he’s not predicting an immediate wave of bank failures—even though others are. And he described the closure of the Fed’s key emergency lending facility as another headwind for banks, rather than an outright disaster.

Still, the loss of the emergency funding program couldn’t come at a worse time, as interest rates remain high, the commercial real estate industry continues to suffer, and depositors could start to get nervous about banks that are struggling to cope in the new environment. Instead of a repeat of 2008, when regulators said they had to step in to save banks that were “too big to fail,” officials could have to come to the rescue due to a “too many to fail” dynamic, with many smaller banks collapsing.

But let’s be clear: “This is a worst-case scenario that comes from a confluence of events,” according to Sedunov. “It’s a possible scenario, but not something I’m losing sleep over just yet.”

Banks’ world of hurt

Banks’ issues really began when the Federal Reserve started aggressively hiking interest rates in March 2022 to combat the hottest inflation in four decades. The move caught some banks off guard, leaving them holding assets—particularly long-term Treasuries—that were quickly being devalued by the rate hikes.

When investors and depositors started getting word that banks were sitting on $1.7 trillion in unrealized losses, largely as a result of this phenomenon, they began looking for the lenders that were in the worst standing. That came to a head last March, when rumors of liquidity issues at Santa Clara-based Silicon Valley Bank sparked the fastest bank run in modern history, forcing the bank to shut its doors. Although the collapse didn’t end up causing a wave of bank failures nationwide, as some predicted it would, it exposed how interest rate pressures are an underlying threat for banks.

As Fortune previously detailed, the dynamic banks are currently experiencing bears an uncanny resemblance to the savings and loan (S&L) crisis of the 1980s and early 90s. More than 2,900 banks went under during the S&L crisis after spiking interest rates devalued the mortgages they held, leaving them with billions in unrealized loan losses.

There is some good news, however: the banking system today is much more robust than it was 40 years ago. And, as Sedunov explained, “we have a handful of banks in distress now. In the S&L crisis, it was hundreds or thousands of S&Ls experiencing distress simultaneously.”

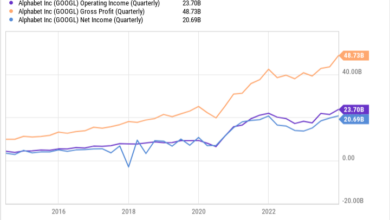

On top of that, banks have begun to address their balance sheet issues amid pressure from regulators. Unrealized losses dropped to $478 billion in the fourth quarter of 2023, a 30% decline from previous quarter, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC) data. That’s the lowest level of unrealized losses since the second quarter of 2022, although it’s still “elevated compared to historical levels,” the FDIC noted.

Banks’ exposure to the struggling commercial real estate (CRE) sector is another factor that’s threatening stability, though. Rising borrowing costs and the decline of in-person work have combined to cripple CRE. In 2023 alone, CRE values fell 20%, lending volumes dropped 46%, and sales plummeted 70%, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

Office values have gone into freefall since the pandemic’s remote-work-fueled exodus from downtowns. That’s left 30% of office buildings essentially “worth nothing,” Fred Cordova, of Santa Monica–based CRE advisory and investment firm Corion Enterprises, told Fortune.

This is a big problem for banks, considering they hold about half of the all commercial real estate debt in the United States. And it’s even worse for smaller regional banks, which own around 70% of that total.

For lenders with big CRE exposure, the timing of the Fed’s decision to ends its emergency funding program also couldn’t be worse: a wave of maturities for 10-year loans signed after the Great Recession is on the horizon. Some $930 billion of U.S. commercial real estate debt, or around 20% of the estimated $4.7 trillion in total CRE mortgage debt outstanding, will mature in 2024, according to Mortgage Bankers Association estimates. That means banks will have to refinance, extend, or pay off these loans.

The situation is so bad that Scott Rechler, co-founder and CEO of the real estate giant RXR, told Fortune that CRE’s issues, coupled with banks’ ongoing problems, could reduce the number of banks in the U.S. by “500 or more” over the next two years as lenders fail and industry consolidation continues.

New York Community Bank (NYCB) is perhaps the poster child for how CRE’s issues can impact banks. The Long Island-based lender held total loans worth $84.9 billion as of December 31, but a whopping 80% of its loans went to the CRE sector, split chiefly among multi-family properties, commercial and industrial properties, and office space.

After NYCB missed earnings estimates and slashed its dividend in January, multiple ratings agencies downgraded its credit to junk, citing its outsized commercial real estate exposure. The bank’s stock price has plummeted ever since, and it’s now betting on a $1 billion lifeline from investors including former Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and Citadel CEO Ken Griffin.

For Villanova’s Sedunov, the dual impact of rising interest rates and CRE’s issues on some banks, like we’ve seen with NYCB, could lead to a worst-case scenario where bank failures become common.

“If you have rates that stay high, if you have continual vacancies or [see] illiquidity start to pop up more in commercial real estate…or people are defaulting on their obligations in larger quantities than expected, then, yeah, we start to think about this becoming more widespread,” he said.

Losing a crutch—because of their greed?

If the pain from rising interest rates, CRE issues, and ongoing industry consolidation wasn’t enough for banks, they also just lost a favorite crutch: the aforementioned Bank Term Funding Program.

The BTFP was hastily thrown together in the middle of the financial panic last March, when the run on Silicon Valley Bank threatened to spread. SVB customers withdrew over $42 billion in deposits on a single day, and while the bank likely had enough assets to weather the crisis, it desperately needed an influx of quick cash to stop the bleeding. Over just two days, the Fed created the BTFP to ease concerns about widespread liquidity issues and help contain the damage from spreading to other banks.

In the short term, it worked. Only three major banks—SVB, First Republic, and New York-based Signature Bank— failed, as the BTFP helped the rest of the sector weather the storm.

“The [bank] runs were becoming a pandemic. The reason that they were able to stop them short like they did is because they put the Bank Term Funding Program in place,” FinPro Capital Advisors CEO Donald Musso, who advises banks on managing their capital reserves, told Fortune. “It was a Band-Aid to solve the crisis.”

The Fed has other ways of injecting liquidity during a bank run, most notably through its “discount window,” but banks hesitate to use it because of a widespread understanding that turning to the discount window can signal serious issues to the market. The BTFP, as a new program, was more attractive because it lacked this stigma. (The Fed, for what it’s worth, is well aware of this perception issue. “We need to do more to eliminate the stigma problem, and we need to make sure that banks are actually able to use [the discount window] when they need to use it,” Powell told the Senate last Thursday.)

The problem was that, in its effort to make sure banks would actually use the BTFP, the Fed was arguably too generous. The BTFP was more than just a Band-Aid: it turned out to be a sweet deal for banks, lending them cash at an attractive interest rate against the face value of their assets, instead of their dramatically reduced market value.

Just months after the program was rolled out, according to Musso, bank CFOs realized it was effectively a free cash machine: they could get low-interest loans from the Fed through the BTFP, lend that same money back to the Fed at a higher interest rate through the central bank’s reserve balance program, and pocket the spread with zero risk.

Villanova’s Sedunov backed up that idea. “A lot of [the lending that] went on with the term funding program…was because banks were able to arbitrage the facility [to] borrow at a rate lower than they could earn on interest,” he said.

BTFP loan balances surged to almost $80 billion in the weeks during and immediately following last March’s bank crisis. But after contagion fears had dissipated, BTFP usage, instead of falling, continued to track upwards throughout the rest of the year, to $163 billion as of last week. After the Fed changed the program’s terms to take away the arbitrage opportunity, however, new loan applications immediately flatlined. That supports the theory that banks’ uses of the BTFP as a free cash machine was part of what led the Fed to sunset a tool originally designed to stabilize the banking sector in emergencies.

“I think because the banks didn’t utilize the BTFP solely for the mission that it was intended for, that’s why we no longer have [it],” Musso said. “I really believe that that was a good chunk of the reason for the death knell of the program.”

The Fed didn’t cite any particular reasons for sunsetting the BTFP in its press release, and didn’t immediately respond to questions from Fortune on why it declined to renew the program.

If banks cashing in on the BTFP’s arbitrage opportunity was indeed what prompted the Fed to end the program, banks’ long-term losses from that decision could overshadow their short-term gains. Without the BTFP, banks have lost an important lifeline as they navigate stresses from interest rate and CRE.

“Having [the BTFP] sunset yesterday was a big mistake. I think [the Fed] should have extended it for at least one more year to make sure that we’re out of this problem,” Musso told Fortune.

Although last year’s SVB-fueled banking crisis is now well in the rearview mirror, there are still lingering threats for the sector. Smaller, regional institutions’ balance sheets are suffering from their commercial real estate holdings and unrealized losses. And SVB showed that social media can help ignite bank runs in a matter of hours, not days—which means having a plan is even more important for banks. The BTFP might be gone, but many of the bigger issues it was created to address are still here.

“I think the term funding program pushed the problem…down the road a little bit, in the sense that it gave banks a lifeline for a short period of time to kind of fix issues that they may have,” Sedunov said.

A worst case scenario: ‘Too many to fail’

Losing the BTFP alone isn’t going to send the banking sector into freefall. But it is more bad news on top of what’s already an ugly landscape for an industry that’s hurting nationwide.

In 2008, the Fed bailed out struggling banks it judged were “too big to fail.” Fifteen years later, sudden destabilization in a banking sector already weakened by stubbornly high rates and CRE exposure—and without access to quick cash through the BTFP—could result in a “too many to fail” scenario, said Sedunov.

“If you have coordinated or correlated failure among many smaller institutions, or medium-sized institutions, that probably will spark some action from regulators to try to fix what’s going on,” he added.

Unlike in 2008, the country’s biggest banks are well-protected from underlying risks: for one, they have relatively little CRE exposure compared to their smaller counterparts. But a flurry of regional bank failures could have just as big of an impact as the failure of a single large one, and the Fed might be motivated to step in and prop them up to contain the ripple effects.

“There’s a certain level of this that banks plan for and prepare for. Banks have loan-loss reserves…it’s a standard cost of doing business. You can be the best lender in the world, but some loans are just going to fail. And so banks prepare for this,” said Sedunov. “It’s when we get to the point that it’s in quantity that’s beyond expectations—that’s when you start to see [problems].”

Source link