Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – A significant underwater discovery has been made off the coast of western France, where divers have uncovered a wall estimated to be 7,000 years old beneath the sea near the Île de Sein in Brittany. This granite wall, measuring approximately 120 meters in length, was found alongside a dozen smaller manmade structures from the same era.

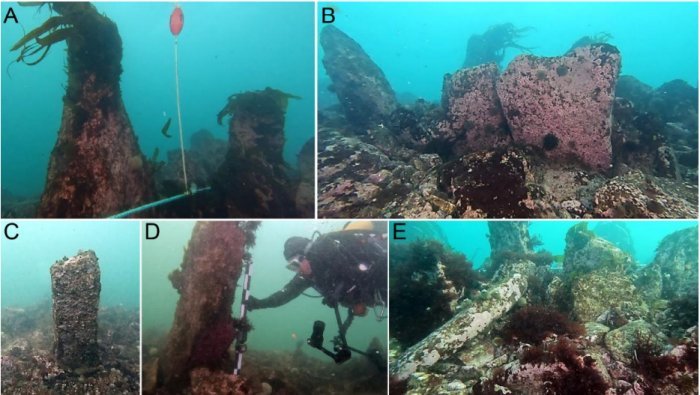

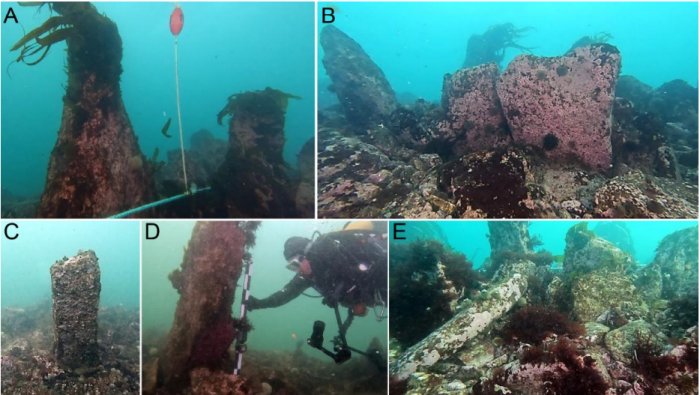

The ancient submerged wall near the Ile de Sein in Brittany, France. Credit: Hal Open Science

Using morpho-tectonic analysis of LIDAR data around Sein Island, researchers identified 11 submerged structures at considerable depths. Subsequent dives between 2022 and 2024 confirmed these are human-built features. Some appear to be fish weirs—structures used for trapping fish, while others may have served as protective barriers against rising seas. Based on relative sea-level data, scientists estimate that these constructions date to between 5800 and 5300 BCE.

Links With Megalithism

These findings are particularly notable because they demonstrate Mesolithic human presence and advanced building skills that predate Brittany’s Neolithic megalithic monuments by about five centuries. The ability to extract, transport, and erect massive granite blocks indicates a high degree of technical expertise and social organization among maritime hunter-gatherer societies during the transition from the Mesolithic to Neolithic periods.

“In Brittany, megalithism appears in the areas where the last Mesolithic indigenous maritime hunter-gatherers met the Neolithic agropastoral populations arriving from the east. The oldest megalithic structures in Brittany are the recumbent menhirs of Belz (Morbihan), erected between 5220 and 4440 cal. BCE and the Neolithic stele of Haut-Mée (Ille-et-Vilaine) erected between 5000–4700 cal. BCE. The Saint Michel tumulus and the oldest megaliths in the Carnac area in Morbihan mark the beginning of Atlantic megalithism around 4700 cal. BCE.

Credit: Hal Open Science

The question of the origin and start of megalithism in Brittany is not clear, however, the possible link with the last hunter-gatherer societies is sometimes mentioned emphasizes that in order to propose a connection between megalithism and marine environments, it is necessary to demonstrate that the oldest monuments were located on the coast of the period in question. It is therefore possible that submerged evidence of a ‘major construction period’ dating from the end of the Mesolithic period in Brittany will one day be found,” the researchers write in their study.

Some scholars have suggested that “the first alignments of standing stones in Brittany may have begun as early as the end of the Mesolithic period and that some of these alignments had functions other than exclusively symbolic. From this period onwards, the quarries from which the stones came were carefully chosen, often located close to the sites.”

According to Professor Yvan Pailler of the University of Western Brittany, this discovery opens new avenues for underwater archaeology and enhances our understanding of how ancient coastal communities were structured. The site was first identified in 2017 by retired geologist Yves Fouquet using ocean-floor charts generated using laser technology.

Links With The Mythical City Of Ys?

The remains now lie nine meters below the current sea level, but would have been accessible when sea levels were much lower thousands of years ago. Researchers believe that some structures functioned as fish traps on what was then foreshore land or as defensive walls against encroaching waters.

Interestingly, this area is also associated with the local legend of the mythical submerged city of Ys, which was said to be protected by great sea walls before being lost beneath the waves.

According to ancient legends, the city of Ys was renowned as one of the most beautiful places in Europe. It is said to have been constructed in the 4th century AD by Gradlon Mawr, also known as Gradlon the Great, who was the king of Cornouaille in Southern Brittany, France.

See also: More Archaeology News

Most accounts locate Ys in Douarnenez Bay. Since it was built below sea level, the city relied on massive sea walls for protection against flooding. Access to its port was controlled by a locked gate, and only King Gradlon had the authority to decide when it would be opened or closed for fishermen.

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Recent Comments