‘A third of the Bible has to do with healing the sick’: How a medical oasis sprung up in Memphis to cover the working uninsured

Wendy Thompson had a handful of problems, beginning with the fact that walking had become excruciating. One of her knees was virtually bone on bone. She was also experiencing consistently blurred vision, a dangerous way to try to get around in the Tennessee snow and ice. But her greatest pain existed at the level of bills and checkbook balances.

Thompson, a home health worker in Memphis tending to patients with special needs, put in full weeks at two jobs, but she still barely made enough to get by. Like hundreds of thousands of Tennesseans, a state that has refused Medicaid expansion, she also had no health insurance, and the cost of care was daunting.

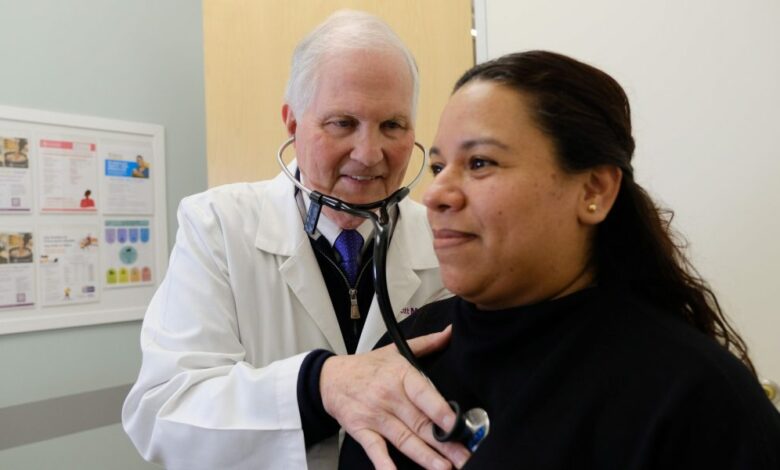

Tending to her medical needs, she told me, was a distant thought. That was before she met Dr. Scott Morris.

“She had fallen and hurt her knee, but it was also crystal clear that she couldn’t see five feet in front of her,” Morris recalled recently, speaking from his office at Church Health, the medical nonprofit he founded more than 35 years ago and through whose doors Thompson walked on a frigid winter day about two months ago. “So I added her.”

What Morris added Thompson to was the upcoming patient list for a biannual event that Church Health cheerfully dubs “cataract-a-thon,” where Thompson would receive needed eye surgery from one of the many area ophthalmologists on hand. In the meantime, Morris, a family medicine physician, had Thompson’sknee x-rayed, determined that she likely required a replacement, and gave her a cortisone injection while he began the process of scheduling her a consultation with an orthopedic surgeon.

When I ask her how the cataract surgery went, Thompson replies, “Baby, I’m wearing my sunglasses! I see colors. I don’t see anything blurry. ”As for Morris,“ Tell him I love him to death. He has been an angel to me.”

The total cost to Thompson? Next to nothing. The cataract surgery was donated. The knee replacement parts, hospital time, surgeon, anesthesiologist, radiologist, pathologist–all donated.

What I am describing sounds an awful lot like the dream of American healthcare. “It’s not magic,” Morris says. “It’s what is possible when people are willing to come together to do the right thing.”

In practice, Church Health is an almost stunning exception to the nightmarish medical industry in the United States. This is a pure nonprofit charity that accepts little government funding, makes no money, and is thriving specifically because Memphis businesses and individual donors contribute to cover its $27 million annual budget. “I’m a professional beggar,” the 70-year-old Morris says wryly.

And what is the cause? To put it simply: Care for the poor.

As a teenager in Atlanta, Morris became deeply interested in two things: his religion and the practice of medicine. He began searching for a meaningful way to connect them. “A third of the Bible has to do with healing the sick,” he told me. “It’s on every page. But I would look around and see what churches did, and there just wasn’t much to it.”

Morris attended both seminary and medical school, and he is an ordained United Methodist minister as well as a board-certified family practice physician. He moved to Memphis after reading that it was one of the poorest major cities in the country, and he created Church Health there with no staff, no money and–on its first open day in 1987–a walk-in total of 12 patients.

Today, Church Health runs primary, dental and eye care, behavioral health, nutrition and wellness services, among others, out of a 1.5 million square foot facility with a full-time paid staff of 250. More than 80,000 Memphians rely on the center for their health needs. But the true magic lies in Morris’s relationship with subspecialists across Memphis who donate their time to diagnose and/or perform needed surgeries, and with hospitals and clinics that willingly write off all costs for Church Health patients who have no other source of reimbursement.

Church Health is also serving a targeted audience: the uninsured. In Memphis, it’s still possible for a person to earn so little that they actually fail to qualify for Medicaid, while commercial health insurance plans remain laughably out of reach.

Tennessee is one of 10 states that have not enacted the low-income expansion of Medicaid made possible through the Affordable Care Act. Six of those states lie in a cluster: Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Despite the coverage gains made during the pandemic, an estimated 25 million Americans remain uninsured, most of them in the South and West.

“It’s the working uninsured,” says Owen Tabor Jr., an orthopedic surgeon who volunteers for Church Health by seeing patients referred to him at his clinic, OrthoSouth, and then operating (if need be) on a gratis basis. “As I’ve heard Dr. Morris say a million times, these are the people who cut your grass and wash your car, and who will one day dig your grave. They’re hard-working people who, because of the American health system, are not insurable.”

In Memphis, Church Health has stepped into that breach. Patients pay on a sliding scale depending upon their income, but most visits, including urgent care visits, are $40 or less. The Memphis Plan, through which patients like Thompson pay $50 per month and then occasionally another tiny copay (think $5), offers enrollment through employers who may not themselves have health plans for their workers, as well as those who are self-employed. And all subspecialty care is free, be it a hip replacement or, say, open-heart surgery.

The program does not serve Medicaid patients, meaning it’s not a Federally Qualified Health Center. There are several FQHCs in the Memphis area (and 1,400 nationally), but because those centers rely heavily on enhanced Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements, they handle a relatively small number of indigent or uninsured patients. And Morris’s network of local subspecialists is exceptional. Says Tabor, “Church Health patients get as good (quality of) care as anybody else.”

Church Health is religious strictly in its roots, and in Morris’s deep conviction about the connection between spirituality and serving the poor. Aside from perhaps wondering about the name on the building, most patients don’t know much about the origin story–nor do they care. In that regard, neither does Morris.

“Most people who work here at Church Health do so because of their faith,” Morris says, “but that’s Jewish, Christian, Muslim–we’re all over the board. We do not work here to impose our faith…We are all called to do the same work.”

Is this sort of system scalable in America? The answer is a qualified yes. Morris says there are about 90 centers in the U.S. that are modeled after Church Health, and he mounts what he calls “replication seminars” twice a year. But those centers will ultimately rise and fall based upon the generosity of the communities in which they reside–and none of them has Morris on staff.

“Dr. Morris is pretty, pretty inspiring. “He talks the talk and walks the walk,” says Victoria Lim, an otolaryngologist who has volunteered weekly with Church Health for nearly a decade. Adds Tabor Jr., “He is an evangelist. I never saw Billy Graham, but if you see Scott Morris in front of a crowd explaining to them why they should give money to Church Health, why they should donate their time–it’d be hard to walk away and say, ‘I’m not going to do that.’”

The idea that the American healthcare system is broken doesn’t shock anyone who’s actually used it. Skyrocketing premium costs and the rise of the deductible as a health industry standard have combined to bleed patients dry financially.

“I was once working uninsured myself,” says Shandra Hubbard, who began as a nurse manager at Church Health two years ago. “I was so afraid of not being able to afford to get sick and go see the doctor. I don’t want anyone to experience that feeling.”

What Morris created in Memphis is a small-scale revolt against what American healthcare has wrought. And although he likely wouldn’t put it that way, the only certainty in this equation is that medical oases like Church Health will continue to be desperately needed in the richest nation in the world.

Carolyn Barber, M.D., is an internationally published science and medical writer and a 25-year emergency physician. She is the author of the book Runaway Medicine: What You Don’t Know May Kill You, and the co-founder of the California-based homeless work program Wheels of Change.

More must-read commentary published by Fortune:

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune.

Source link